In the latest edition of this popular video series on the state of the current economy, Brett Davis, President and CEO of National Indoor RV Centers, explains the factors that led to the Silicon Valley Bank collapse and how it affects RVers, businesses, and the global economy.

Greetings National Indoor RV Centers family of customers and friends.

Since my last video a year ago, when the Fed Funds rate was hovering right at zero, the Federal Open Market Committee has raised the Fed Funds rate 9 times to its current target range of 4.75% to 5.00%. As the saying goes: whenever the Fed hits the brakes, someone goes through the windshield. We all know it. The fed knows it. We just never know who it’s going to be until it happens.

In the wake of all these rate increases by the Fed, I was preparing to share my thoughts on the current state of our economy and the RV market, and where I suspect they are both headed in the future.

However, I have just returned home from a marathon of back to back to back motorhome rallies in Georgia, where for three weeks the questions posed to me about Silicon Valley Bank, and how sound is our banking system, were relentless. And, to be completely transparent, it wasn’t just the plethora of questions I received during my three weeks of rallies which piqued my interest in the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, or SVB for short. I was already following SVB with both intrigue and concern. Having owned a bank years ago, I was following SVB with intrigue, because it wasn’t your traditional bank. But, I was also following it with some concern, because I’m a limited partner in one of those venture capital funds who did all their banking with SVB. Needless to say, for all those reasons I called an audible to, and decided to share my musings on SVB and our banking system, before sharing my thoughts on the economy and the RV market.

Think of a lofty Jenga tower when discussing complex systems like our banking system. Eventually, one ever so slight miscalculation, one puzzle piece too many, and fatality strikes.

“Eventually” is the key word. Exactly which puzzle piece will do it, we can’t know ahead of time.

But, before the tower collapses, each puzzle piece forms points of instability. Small weaknesses where a failure could begin. Sooner or later, it will be one puzzle piece too many. But, no one knows when, or which piece, will be “the big one” which brings the whole tower down.

These points of instability seem to be piling up lately. Last October, the UK had a brief bond crisis when some budgetary changes revealed rather questionable pension fund activities. Then the bankruptcy of crypto exchange FTX showed how supposedly “trustless” assets can require a lot of trust.

During the second weekend in March, we witnessed the second and third largest bank failures in US history: Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. And yes, several other banks, including First Republic and PacWest, look to be very shaky as well. These banks have similar features to SVB, as well as exposure to Crypto based businesses. However, I also think these banks are very unique. Unicorns if you will. I don’t believe you can paint the current 4,844 FDIC insured banks in our country with the same brush as these banks. Nor do I believe they are representative of the contagion which affected our entire financial system back in 2008. Let alone any contagion which would impact the RV industry whatsoever.

Fortunately, regulators responded swiftly to stabilize both situations. Personally, I believe 99% of all banks are just fine, but we should all be paying attention to make sure our bank isn’t in the 1%, because important things are happening.

And no, not for a minute do I think this is 2007/2008 all over again. But, it’s also not nothing.

Let’s start with what we do know. We know SVB had problems with both their assets and their liabilities.

It’s important to remember, whenever we deposit our money into a bank account, we are really lending our cash to the bank. It truly is a loan transaction, with us as the lender and the bank as the borrower. In fact, our deposits appear as liabilities on the bank’s balance sheet.

This is how banking works. In its simplest terms, the bank borrows money from us, and then lends it to someone else. If all goes well, the bank profits from the difference between the interest it pays its depositors, and the interest it receives on the loans it makes.

Those loans support small businesses, they help consumers buy cars, homeowners buy their dream homes with mortgages, and a whole lot more. Banks also loan money to the federal government by purchasing Treasury securities. They don’t yield as much as a loan, but they are also lower risk. However, they are not zero risk, as we’ll see in a minute.

Running a bank is truly a balancing act, because the bank’s assets, which are really loans, and the bank’s liabilities, which are really deposits, have different maturities. People can demand their money back at any time, but the bank can’t call in its loans, at least not very quickly. It works only because most people leave their balances in place most of the time. This is where having a loyal, diversified depositor base really helps reduce the risk profile of a bank.

The absence of a loyal, diversified depositor base proved to be a real problem for SVB. Most of SVB’s deposits came from a relatively small group of venture capital firms who “recommended” to the startup companies they funded to keep their cash balances at SVB. The nature of these startup companies’s deposits added an additional degree of difficulty to SVB’s balancing act beyond a highly concentrated depositor base controlled by a handful of Venture Capital funds.

Startups are just that… startups. Companies with an idea, but no capital to bring their ideas to fruition. Venture capital funds provide their startups with all their projected cash needs right up front. Meaning, on day one the startup has a pile of cash, operating expenses, and no revenues. The hope is revenues for their idea, their new product, will grow to meet and exceed their operating expenses, and thereby start producing a profit. It’s not uncommon for this to take years. It took over nine years from its founding for Amazon to turn its first profit. In Amazon’s 58th quarter of existence it finally made a profit larger than its previous 57 quarters combined. That’s 14 years and two quarters after startup. Here are a few more companies we all know. It was 5 years before FedEx was able to turn a profit, and 7 years before ESPN became profitable. From its founding it was 17 years before Tesla made its first dime. From their founding to profitability startup companies are burning through the cash they were funded with at startup. Venture capital funds project what they believe the burn rate of their startups will be until they reach profitability, and assuming their ideas prove to be economically viable, they fund their startups with that capital right up front, and in turn those startups deposit their funds in whichever bank their sponsoring venture capital fund recommends.

In addition to their highly concentrated depositor base of venture capital funds, SVB had to also contend with the “burn rate” of the startups these firms had funded, which now comprised their depositor base. Clearly this was far from a traditional depositor base for a bank.

As a part of the macro slowdown in 2022, which slowdown was the intended result of the Fed raising interest rates, the burn rates of these startups actually accelerated. SVB poorly forecasted the accelerated burn and the resulting draw-down needs of their depositors. Which, resulted in SVB not having the liquidity to pay them all.

What SVB did have was a lot of longer-term Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities it had purchased when their deposits ballooned in 2020 and 2021. Which, was before the Fed started raising interest rates in March of 2022. If you remember from my RVs, the Economy and You! Update 2, Part 1 video from last year, when interest rates rise the market value of bonds falls. Which isn’t a problem if you can hold the bonds to maturity. However, it can be a big problem if you need to sell them in order to cover your depositor’s withdrawals.

Rising interest rates put SVB in a tough spot, which got tougher as depositors withdrew their money in the weeks leading up to SVB’s failure on 3/10/23. Here is an excerpt from my video last year which is truly appropriate in SVB’s case.

Insert 0:57 to 1:11 from RVs, the Economy and You! Update 2, Part 1

SVB’s failure started gradually with by poorly forecasting their depositor’s burn rate, which is best explained by SVB’s former President in his letter to investors:

“While Venture capital deployment has tracked our expectations, client cash burn has remained elevated and increased further in February, resulting in lower deposits than forecasted. When we see a return to balance between venture investment and cash burn – we will be well positioned to accelerate growth and profitability,” noting SVB is “well capitalized.”

SVB was forced to sell some of their Treasuries and Mortgage-Backed Securities in order to fund these withdrawals. With each sale of their treasuries SVB was forced to recognize the inherent market losses created by rising interest rates over the past year.

SVB’s portfolio of Treasuries was yielding an average 1.79%, which was far below the 10-year Treasury yield of around 3.9%. These sales forced SVB to recognize a $1.8 billion loss, which it would need to replace through raising more capital by selling more shares in the bank.

Late in the day on Wednesday March the 8th, SVB spooked investors and depositors with a belated attempt to raise additional capital by announcing the sale of $2.25 billion in common equity and preferred convertible stock to replace the capital it had just lost. SVB’s stock ended the day down 60%, as investors fretted further deposit withdrawals may push the Bank to raise even more capital.

In what will probably turn out to be the most ill-advised conference call in the history of banking, in a failed attempt to head off a run on his bank, the President of SVB held a conference call with the bank’s twelve largest Venture Capital funds at 11:30am PST on Thursday, March 9th. The purpose of his call was to reassure the bank’s largest depositors their deposits were safe, the bank was healthy, and in not so many words he essentially conveyed the bank could withstand anything…except a run on the bank.

Well, as it turned out, the dozen Venture Capital funds were calm, until SVB’s President instructed them to remain calm three times during the call. Within 30 minutes of the call ending, $42 billion of withdrawal requests hit the Bank’s wire desk. That bears repeating. $42 billion of SVB’s $175 billion in total deposits had just requested their money back! The Bank did manage to fulfill the $42 billion in withdrawal requests, and then they promptly closed the bank early. Which, led to the lines of people we’ve all seen pictures of, as Venture Capital funds instructed their companies to go to the bank to withdraw their money in person.

However, Thursday’s $42 billion in withdrawals pales in comparison to what was about to happen on the morning of Friday March the 10th. Michael Barr, vice chair for supervision at the Federal Reserve testified before the Senate banking Committee, and I quote:

“That morning, the bank let us know that they expected the outflow to be vastly larger based on client requests, a total of $100 billion was scheduled to go out the door that day.”

Consequently, SVB never opened on Friday as the combined withdrawal figure of $142 billion represented a staggering 81% of SVB’s $175 billion in deposits. Think about that. $142 billion in withdrawals in less than 24 hours, which is why the FDIC jumped in. The dizzying pace at which money left SVB shows just how quickly bank runs can happen with the technology of today’s world. Social media heightens panic, and online banking allows for quick transactions.

The speed at which SVB failed is unique. And, to highlight this point, think about this. 538 banks have failed since 2008, and yet few of us knew about them. Life went on as normal. But, $142 billion in under 24 hours severely limited the FDIC’s options and brought with it a lot of publicity.

I readily admit, I wasn’t a fan of how the Fed handled the bailouts of banks in the 2008 crisis, but I do believe they did it correctly this time. While you may or may not be a fan of SVB’s customers (tech startups) they were and are very important to the US economy. We need them! I believe they are truly “systemically important.” The FDIC gave SVB customers full access to their deposits, so they made payrolls and life went on. I believe this was appropriate, and please let me explain.

The World’s five most devastating financial crisis are the Credit Crisis of 1772, the Great Depression of 1929 to 1939, the OPEC Oil Price Shock of 1973, the Asian Crisis of 1997, and the Financial Crisis of 2007/2008. I have lived through three of those five crises, but the Financial Crisis of 2007/2008 really stands out, and not because it’s the most recent. It stands out because of how it was handled.

The Troubled Asset Relief Fund, better known by its acronym TARP, was instituted by the US Treasury following the Financial Crisis of 2007/2008. TARP stabilized our financial system by having the government purchase mortgages backed securities and bank stocks. That’s right, the government purchased equity in banks and other financial institutions. From 2008 to 2010 TARP invested $426.4 billion in banks and other financial institutions and recouped $441.7 billion in return. But, part of what made TARP so controversial was the shareholders were not wiped out, nor were any people fired. This is why I wasn’t a fan of how the Fed bailed the banks out in 2008.

But, this time around, unlike 2008, the FDIC did wipe the shareholders out, and they did fire the senior management of the bank. When you mess up that spectacularly, you should be fired! And honestly, I will say the same thing about Federal regulators and their ridiculous stress tests. It is hard for me to believe they could have truly been that blind!

As pointed out in the Wall Street Journal on March 15th, even if midsize banks had been subjected to the same scrutiny as large banks it’s very doubtful it would have prevented SVB’s failure. Why? Because the tests failed to encompass the very scenario which ultimately led to SVB’s demise… large and rapid increases in interest rates.

In its February 2022 Stress Test Scenarios, the Fed’s “severely adverse scenario” asked banks to assess their riskiness over a three year horizon assuming the 3 Month Treasury stays near zero percent while the 10 Year Treasury declines to 3/4 of 1% during the first three calendar quarters of 2022. Think about that for a minute. In February 2022, the Fed instructed banks to assume zero percent interest when creating their worst-case scenarios, and then starting the very next month in March of 2022 the Fed promptly raises rates five times to 4.5% interest by the end of 2022. The biggest rate increase in a single year since 1980.

Then in February of 2023, when the 3 Month Treasury was already at 4.5%, the Fed shockingly instructs banks to assume the 3 Month Treasury falling to near zero percent by the 3rd quarter, and the 10 Year Treasury falling to 1/2 of 1% by the 2nd quarter in their worst-case scenarios. This truly makes reason stare! Is this how anyone who was warm and had a pulse would project and prepare for a worst-case scenario? By pretending they’re really not raising interest rates? Is this truly how they’re going to regulate our banks? Talking out of both sides of their mouths? Throughout my business career I have always believed no enemy is worse than bad advice.

The Fed’s 2023 severely adverse scenario assumptions bore no relationship to reality. Do the Fed’s bank regulators not talk with each other? Or, at a minimum at least read about what is going on with their own monetary policies? They have been raising rates for a year! The regulatory executives who somehow managed to overlook this should be fired just like the senior management of SVB was. But, we all know that’s not going to happen. Passing additional laws and regulations isn’t going to help if the regulators are incompetent. There were more than enough laws and regulations to have prevented this. In my opinion, firing the senior management at SVB is just a start in cleaning house.

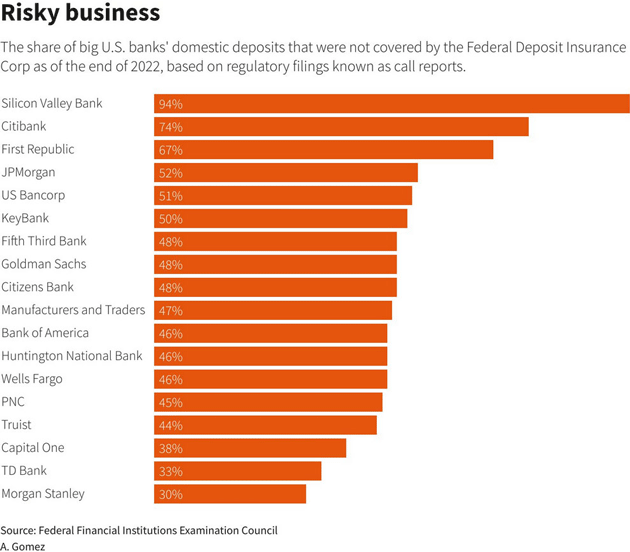

Moving on, I don’t know whether this is fascinating, or truly troubling, but 94% of the deposits at SVB were above the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit, and thereby uninsured.

The $250,000 insured amount was certainly no secret. It is plastered all over bank walls and appears in almost every account document anyone signs. It was crystal clear larger balances were at risk if the bank failed. But, SVB depositors, some of the most sophisticated investors on the planet, simply didn’t seem to care, or believed the limit didn’t apply to them. As it turned out, it didn’t.

Many, if not most, banks offer an Insured Cash Sweep, or ICS service. I know all our banks offer it. ICS accounts extend FDIC insurance by breaking up large cash deposits and then distributing the smaller amounts to multiple banks. ICS accounts simply allow businesses access to FDIC coverage above the standard $250,000 limit. It’s a safe and simple thing to sweep excess amounts, and bring them back in as needed to clear checks. In today’s world, keeping millions of uninsured dollars in the same bank just makes no sense. Yet, it was very common at SVB. And, it wasn’t just SVB. Even our largest banks have more uninsured than insured deposits. And yes, from the chart you can see how SVB led the way with 94% of their deposits being uninsured. 20% more than the next closest bank, which happens to be the international behemoth Citibank. But, let’s put this into perspective. Citibank has 673 locations in the United States and 1,800 branches scattered throughout 160 other countries versus SVB with just 17 branches. I can easily understand why depositors in other countries would care far less about the FDIC insurance limits than our domestic depositors. My point, SVB was a unique bank. It was a unicorn that wasn’t representative of our banking system, or the contagion which affected our entire financial system back in 2008.

Source: Reuters

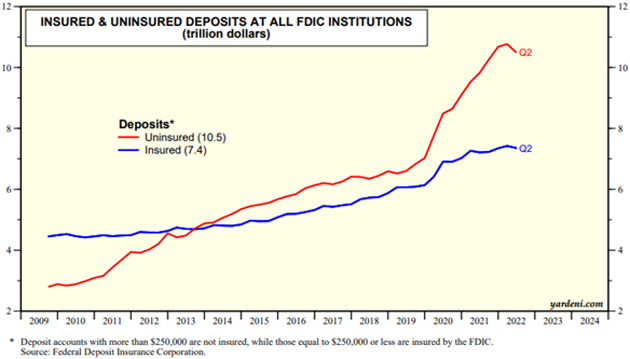

These excessively high uninsured balances haven’t always been the case. Look at this chart from Yardeni Quick Takes comparing insured and uninsured deposits for all US banks.

Source: Yardeni QuickTakes

With the current $250,000 deposit insurance limit, US banks had $10.5 trillion dollars in uninsured deposits halfway through 2022 versus only $7.4 trillion insured. In fact, a majority of deposits have been uninsured for a decade now, but notice how the line bends sharply upward in 2020. Why? Well, it’s because it coincides with the Fed’s stimulus, plus all the various COVID fiscal programs. However, there was, and there is still nothing requiring people to keep all that money in banks.

This certainly seems like a problem to me. In the case of SVB, regulators used a “systemic risk” emergency clause to cover otherwise uninsured deposits. FDIC was able to do this without breaking its own finances because SVB had good assets in the form of its Treasury bond portfolio. They were just illiquid.

Question: would the same thing happen at any other bank? Well, it certainly hasn’t in the past. If you comb through the FDIC’s failed bank database you will see depositors in smaller failed banks often losing half or more of their uninsured balances. Even those who received partial recoveries took years. You see, those banks and their depositors weren’t considered “systemically important.”

Our government is giving a handful of mega-banks a massive privilege our small community banks clearly don’t get. This may produce more systemic risk, not less. I really don’t think we want to know the answer to that question, but I’ll bet someday we going to find out.

This is additionally unfair to our small local banks, which are often community pillars in places the mega-banks don’t serve. According to the FDIC’s 2020 Community Bank Survey, community banks held 30% of all Commercial Real Estate loans, despite only having 12% of the banking industry’s total assets. This doesn’t include all sorts of other loans to made to locals the large banks don’t make. We need these small banks, but then the Fed handicaps them?

Think of the uncertainty this is creating. Are your balances above $250,000 protected? Well, if they’re deposited at one of the top dozen largest banks, the answer is certainly yes. The dozen largest banks will either not be allowed to fail, or depositors will receive full coverage under that systemic importance provision.

But, what about small community banks? If yours fails, your uninsured deposits are supposed to take a haircut. And, probably a big one. Then there’s a giant gray area of medium sized banks or regional banks, which may or may not be considered systemically important. SVB wasn’t considered systemically important… until it was. No one knows what to expect.

This is simply untenable. Sure, no one wants to see anyone get hurt, but at some point, people have to bear the consequence of their decisions. If a company decides to hold $50 million or more in uninsured bank deposits—as several SVB customers did—should they be made whole when the bank fails? Is that fair to other businesses who managed their cash prudently? What incentives does it create? I don’t think we want to experience the answer to that question, nor do I think we want to live with a banking system comprised of just a dozen mega-banks. Unless you are a very large corporation, or an uber wealthy individual, we will all be standing in line, holding our cups out, until it’s our turn. It could take months to find out if we are lucky enough to borrow any money. Bottom line, after the failure of SVB, I now ponder what is considered systemically important versus what is considered systemically unfair?

I feel it’s important to note just how much power the Fed really yields. The Fed not only dictates our country’s monetary policies, but it also regulates our banks. Yes, it does works alongside the FDIC, the OCC, and the Treasury, to ensure the stability of both our banks and our banking system as a whole. In the wake SVB’s failure it seems to me this process needs improvement, or at least better communication amongst themselves inside the Fed.

Lastly, throughout my banking career, in fact my entire business career, it has always seemed to me like the Fed was fighting the last war. After the financial crisis of 2008, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, which imposed many new rules and requirements, all intended to prevent another such event. And, so far it has worked: We haven’t had another subprime mortgage crisis.

But, as is always the case with regulatory legislation, Dodd-Frank has holes in it. Plus, it created unintended side effects. Not to mention a baffling application of the rules by the regulators themselves.

Dodd-Frank focused primarily on reducing bank credit risk. Specifically, the kind of mortgage lending activity which brought down a number of large institutions and countless small ones. These new requirements encouraged, or in some cases outright mandated, banks hold more Treasury bonds. In theory they would have no credit risk. Unfortunately, they never took into account the interest rate risk banks would be taking on by holding those bonds.

In truth, they did just the opposite. They let banks put long-term Treasuries and mortgages in a special regulatory bucket that didn’t require marking those assets to market against their capital base. They would only be marked to market when they actually sold. If bank management and regulators couldn’t see this as a problem, it begs the question… who’s watching the watchers.

Everything was fine, until it wasn’t. When the Pandemic hit both fiscal and monetary stimulus poured in, bank deposits ballooned, banks used those deposits to purchase treasuries and mortgage backed securities, supplies of virtually everything were greatly reduced, demand skyrocketed, and inflation soared. The result of all of this put the Fed in a bind. The obvious answer was to tighten credit by raising interest rates. However, the very same Fed who was tightening credit and raising interest rates, was also overseeing a banking industry which wasn’t prepared for this scenario.

Now the Fed has put themselves into yet another bind. Will the Fed push more banks over the edge by continuing to raise rates? Or, will the Fed not raise interest rates and risk letting inflation take off again? More to come on this when I find time to shoot a video on our economy.

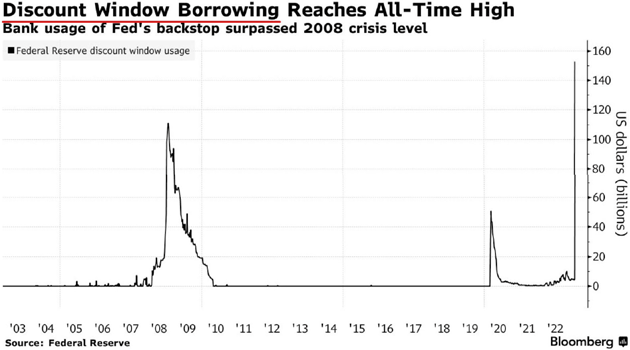

And, despite the huge increase in their balance sheet during the second week of March, I believe the Fed will continue quantitative tightening. As the chart shows, the increase came not from a stealth quantitative easing, but from banks pledging their long-term assets for new liquidity. While obviously a sign of stress—it’s also exactly how the system is designed to work in times like these.

Source: Bloomberg

And, it’s not just borrowings from the discount window. The Fed’s new Bank Term Funding Program allows banks with unrealized losses in their Treasury securities to pledge them as collateral and get cash from the Fed. Presto, instant liquidity for those who overloaded on Treasuries and/or forgot to hedge the risk. Depending on how far down the banking food chain this goes, it may solve the immediate problem. However, normal bank insolvency, like the 538 banks which have failed since 2008, will still result in bank failures. And, unfortunately, depositors at small banks will find out.

Of course, this is unfair to the prudent banks. The Fed is essentially rewarding unwise risk-taking. The fact this is done within the regulatory guidelines doesn’t mean there is no risk, just bad guidelines.

I just can’t stop thinking about that lofty Jenga tower. It’s not just banking. Commercial real estate, the markets, global trade, a clearly slowing manufacturing base, the massive rise in sovereign debt worldwide, negative growth in our money supply, and so much more. Eventually… it will be one puzzle piece too many? But, that puzzle piece isn’t going to be Silicon Valley Bank, or Signature Bank, or any of the other routine 35 to 40 bank failures a year we never hear about.

I want to thank all of you who have taken time out of your lives to listen to my thoughts. When I find the time, I will be back to share my thoughts on the economy, the RV market, and what the future may look like for both. I wish you all safe travels, and only the best. Thank you for watching.